Figure 1. Age of dog when first became coprophagous

OJVRTM

Online Journal of Veterinary Research©

Volume 7 : 17-25, 2003.

Department of Veterinary

Clinical

Sciences1,3and

Department

of Veterinary Comparative Anatomy, Pharmacology, and Physiology2,

Washington State University, Pullman, WA, 99163.

Hofmeister EH, Cumming MS, Dhein CR, Owner Documentation of Coprophagy in the Dog, Online Journal of Veterinary Research 7: 17-25,2003. The purpose of this study was to characterize coprophagous dogs by age, sex, breed, weight, diet, housing, social standing, habitualness, and age of onset of coprophagy and to determine owner perceptions of coprophagy and treatment effectiveness. Internet communications and World Wide Web pages were used for solicitation and collection of data. Results showed that dogs which engaged in allocoprophagy had different access to feces than other dogs and weighed less than dogs which did not engage in autocoprophagy. 53 percent of coprophagous dogs were habitual in the behavior. 63 percent of coprophagous dogs began engaging in coprophagy prior to 12 months of age. Treatments owners considered most effective were picking up feces, muzzling or distracting the dog, and removing access to feces.

KEYWORDS:

Coprophagy, feces, dog, survey

Coprophagy is the behavior of eating feces. It is a common complaint of owners to their veterinarians, yet little to no research has been done on this behavior. Coprophagy can be subdivided into the classifications of autocoprophagy, allocoprophagy, and xenocoprophagy. Autocoprophagous animals consume their own feces, allocoprophagous animals consume the feces of animals of the same species, and xenocoprophagous animals consume feces of animals of a different species (Soave et al, 1991). In rodents, rabbits, and possibly piglets and foals, coprophagy is a source of nutrients excreted in the feces which are not utilized efficiently in the gastrointestinal tract (Barnes et al. 1957).

Numerous etiologies for coprophagy in the dog have been proposed and include normal behavior, frequency of feeding, diet, boredom, learned behavior, innate behavior, nutritional deficiency, allelomimetic, pathologic, pharmacologic, positive reinforcement, social interaction, stress, attention-seeking, and idiopathic (McCuistion 1966, Kronfeld 1973, Campbell 1975, Georgi et al. 1979, Houpt 1982, McKeown et al. 1988, Pijls et al. 1988, Hubbard 1989, Cloche 1991, Houpt 1991, Beerda et al. 1999) Normal behavior means that coprophagy is normal to domestic dogs and does not result from any change or alteration in their environment or physiology. Frequency of feeding has been hypothesized to cause coprophagy because the dog’s eating schedule is different in many households compared to their schedule in the wild. It has also been proposed that a change in diet to include less carbohydrates can cure coprophagy (McCuistion 1966, Kronfeld 1973, Campbell 1975, McKeown et al. 1988, Cloche 1991). Owners have suggested that boredom contributes to coprophagy because it “gives the dog something to do”.

Anecdotal reports exist of dogs learning to engage in coprophagy from observing other coprophagous dogs. Innate behavior includes maternal behavior such as ingesting the puppies’ feces (Hubbard 1989, Houpt 1991). Nutritional deficiencies such as thiamine have been shown to cause coprophagy (Read et al. 1981). The allelomimetic hypothesis proposes that dogs observe the owners removing feces from the yard and imitate this behavior (Houpt 1991). Several pathologic conditions such as exocrine pancreatic insufficiency may cause coprophagy (Houpt 1982, McKeown et al. 1988, Pijls et al. 1988, Hubbard 1989). This is thought to occur because of an increase in fat content or a higher content of undigested food in the feces, making it more palatable. There have been anecdotal reports of dogs becoming coprophagous after receiving medications such as glucocorticoids and anticonvulsants. The hypothesis that dogs engage in coprophagy because the feces tastes good and thus is inherently reinforcing has been proposed (Cloche 1991).

It is possible that social interactions, such as a submissive dog eating the feces of a dominant dog, contribute to coprophagy (Campbell 1975). It has been shown that stress can be a contributing factor to initiating coprophagy (Beerda et al. 1999). Anecdotal reports exist that coprophagous dogs have clinicopathologic abnormalities which may be related to their coprophagous behavior (Landsberg 1997). These abnormalities include low trypsin-like immunoreactivity or abnormalities in folate, cobalimin, or other nutrients (Landsberg 1997). Finally, it is possible that the etiology for coprophagy is not included in any of these and may be idiopathic or multi-etiologic. It is impossible to comment, without being dogmatic, on the plausibility of these proposed etiologies, as no peer-reviewed research publications exist which address this topic.

To our knowledge, no objective

data

regarding the characteristics of coprophagous dogs has been published

in

the veterinary literature. The attitude of owners towards

coprophagy

in their dogs is also unknown. The purpose of this paper is to

determine

the characteristics of coprophagous dogs and owner perception of

coprophagy

in their dogs.

Sample Population: The target population for the study was dog owners who used the internet. Dog owners were solicited from the internet Usenet newsgroups of rec.pets.dogs.health, rec.pets.doc.behavior, alt.vetmed, and rec.pets.cats.heath+behav; from an information website located on the Washington State University College of Veterinary Medicine web server; and from the VETPLUS-L listserv. Dog owners were asked to email the author to request the study web page address (http://www.vetmed.wsu.edu/pets/cover.htm) that provided an introduction to the study and instructions for participation. If a questionnaire did not come from an individual who sent a corresponding email to the authors, it was deleted. This was employed in an attempt to exclude any individuals who might abuse the process or provide misleading responses. Multiple announcements were made to the Usenet newsgroups to increase response rate. The web page survey was open for 2 months.

Survey Design: The survey form was developed and adapted for use via computer-based electronic communication. The survey is available as the Appendix. The survey was previewed and critiqued by professionals familiar with study design, epidemiologic studies, internet communications, and database design before initiation of the study.

Coprophagous dogs were divided into 7 mutually exclusive groups on the basis of the type(s) of coprophagy in which they engaged: autocoprophagous, allocoprophagous, xenocoprophagous, auto- and allo-coprophagous, auto- and xeno-coprophagous, allo- and xeno-coprophagous, and a group that included dogs which engaged in all three types of coprophagy. A separate ‘total coprophagous’ group was created which included all coprophagous dogs. “Habitual” was defined as dogs which always engage in coprophagy when presented with the opportunity. A fill-in section was provided for owners to explain why they believed their dog engaged in coprophagy. Because this question was fill-in, specific definitions, such as what “kenneled frequently” means, could not be made.

Data Analysis: All data submitted through the web page form were downloaded into a relational database. Three identical analyses were applied for each of three response variables (xenocoprophagous, allocoprophagous, autocoprophagous). In each case, first a logistic regression on the following 11 independent variables was used to choose those independent variables which may stay in the final model: location, breed, sex, neuter status, age, weight, diet, housing, multiple dogs in the household, dominance, and access. Forward selection method was used. All those variables chosen in this step were used in the next step.

In the second step, all those variables chosen after step one, plus the remaining independent variables (habitual, owner attitude, talk to vet, vet help, treatments tried, treatments worked, and whelping status), were put into a logistic regression model. Using the same selection method, all those independent variables which were significant were determined. Overdispersion was considered in the first two steps.

Since either there is no

significant

effect in xenocoprophagous cases or there are two significant effects

in

other two cases, the correlation between one significant independent

variable

and the dependent variable after adjusting the other significant

independent

variable was tested using Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test. The

final step was to test the association between two significant

independent

variables using Fisher Exact test. The above tests were done in SAS 8

(SAS

Institute Inc., Cary). Significance was defined as p<0.05.

1252 entries were recorded by the end of the study period. 54 entries were incomplete and were deleted. 41 entries were deleted for not having sent a corresponding email to the authors, leaving 1157 records for analysis. 802 owners completed surveys for 1157 dogs. 295 dogs were noncoprophagous, 862 dogs were coprophagous.

Significantly more allocoprophagous dogs had access to other dogs’ feces than non-allocoprophagous dogs. There were significantly fewer autocoprophagous dogs in the 51-70lbs and 71+lbs groups and significantly more autocoprophagous dogs in the 11-20lbs and 21-35lbs groups. There were no significant differences between coprophagous and non-coprophagous dogs for gender, breed, age, diet, housing, or presence of other dogs in the household.

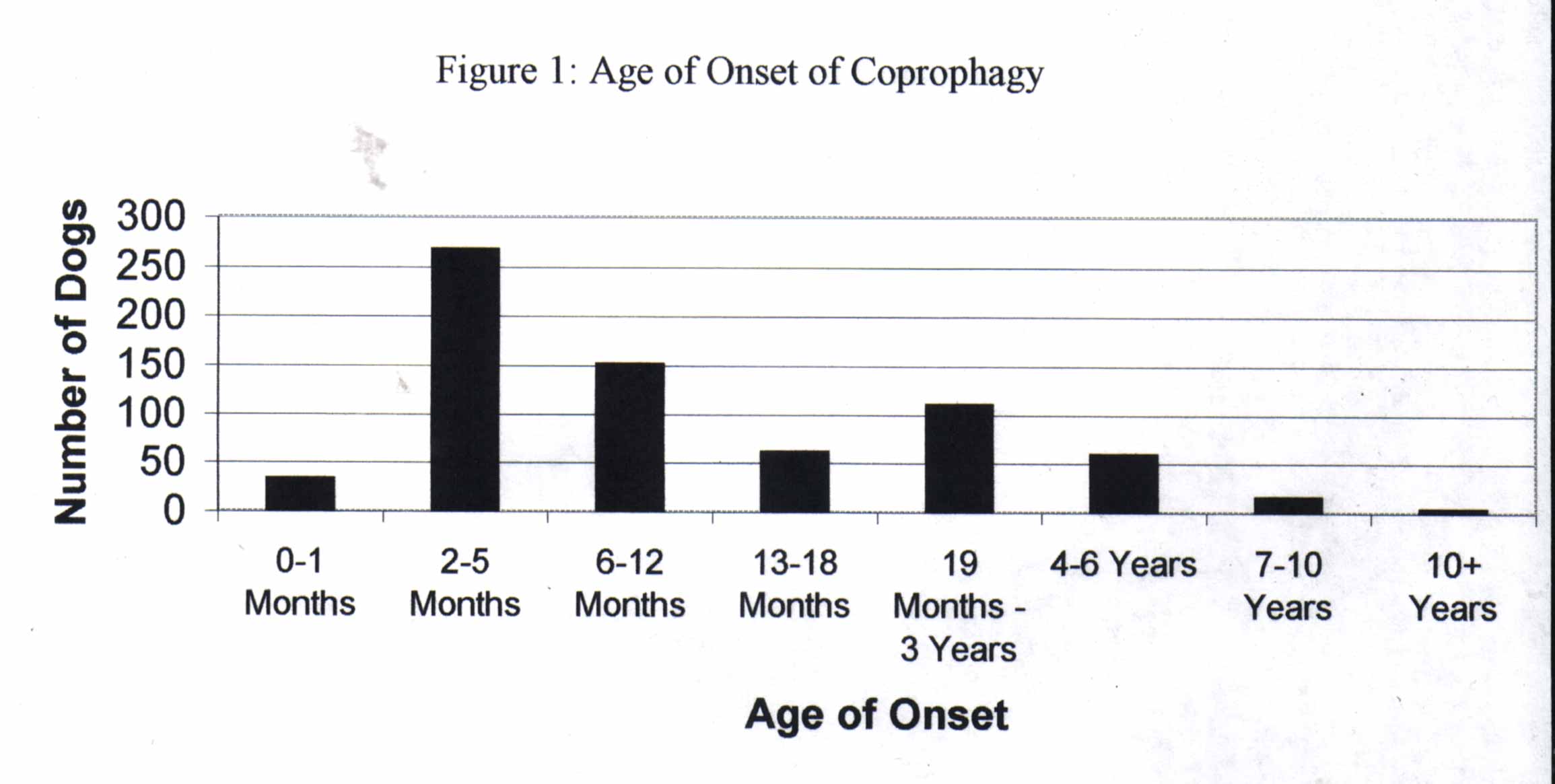

462 (53%) coprophagous dogs

were

habitual in the behavior. 543 (63%) of coprophagous dogs began

engaging

in coprophagy prior to 12 months of age (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Age of dog when first became coprophagous

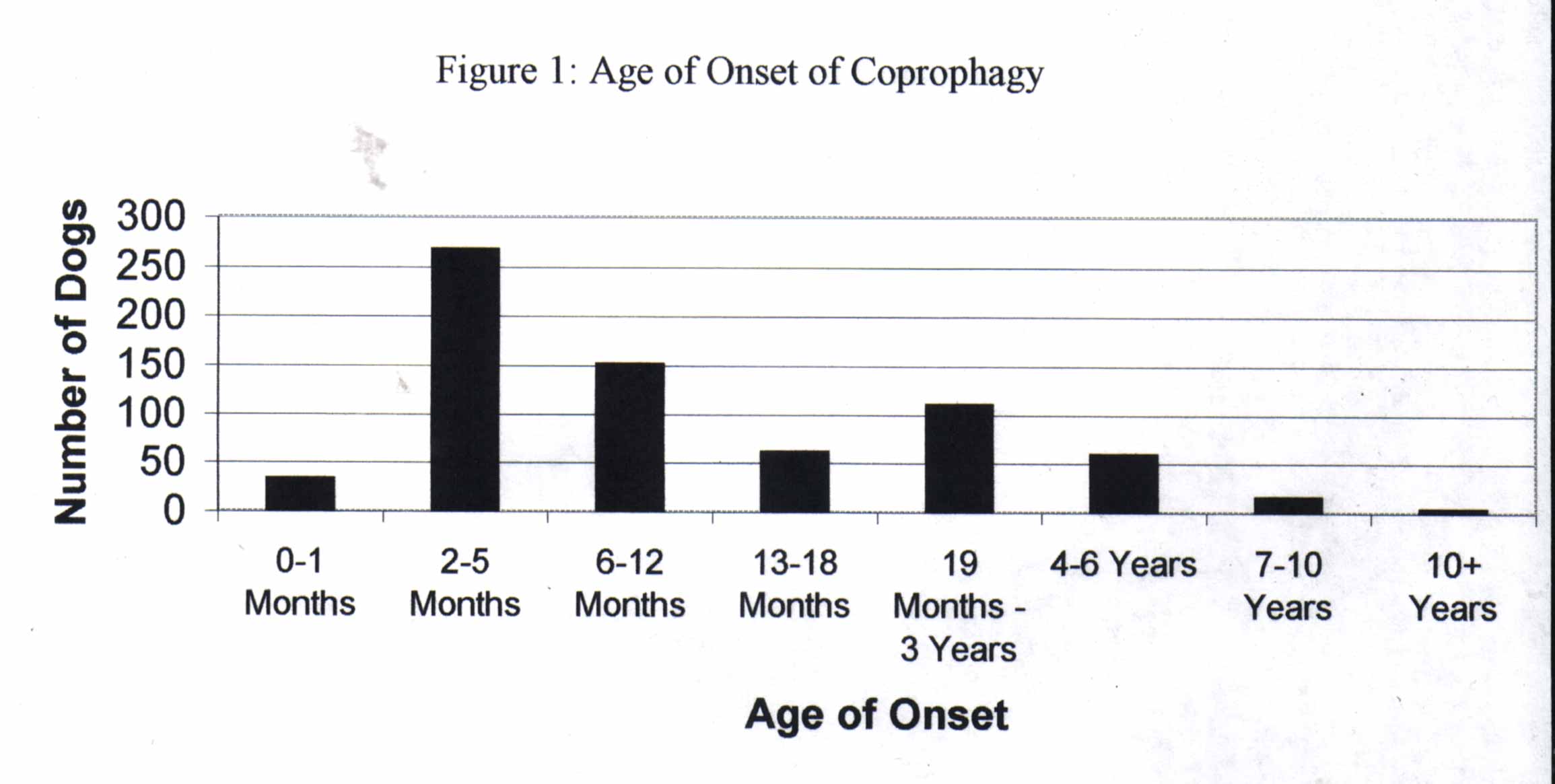

As the age of onset increased,

the

incidence of habitualness decreased (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Age of dog at onset of coprophagy compared with percent incidence of

habituation.

Treatment efficacy is summarized

in Table 1. “Other” was a fill-in

choice

which primarily included removing access such as putting the cat litter

box out of reach (78/86; 91%). Other fill-in treatments which

worked

included diet change, brewer’s yeast, glutamic acid, tomato

sauce/paste,

Missing Link ® (Designing Health Inc, Valencia), alfalfa pellets,

positive

reinforcement for not engaging in behavior, shock collar, Prozyme ®

(Prozyme Products LTD, Lincolnwood), vitamin B12, and carrots.

Table 1: Treatment summary

|

|

successfully treated/ Number of animals given treatment |

|

|

|

|

|

|

(Alpar Laboratories, La Grange) |

|

|

|

(8 in 1 Hauppauge) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

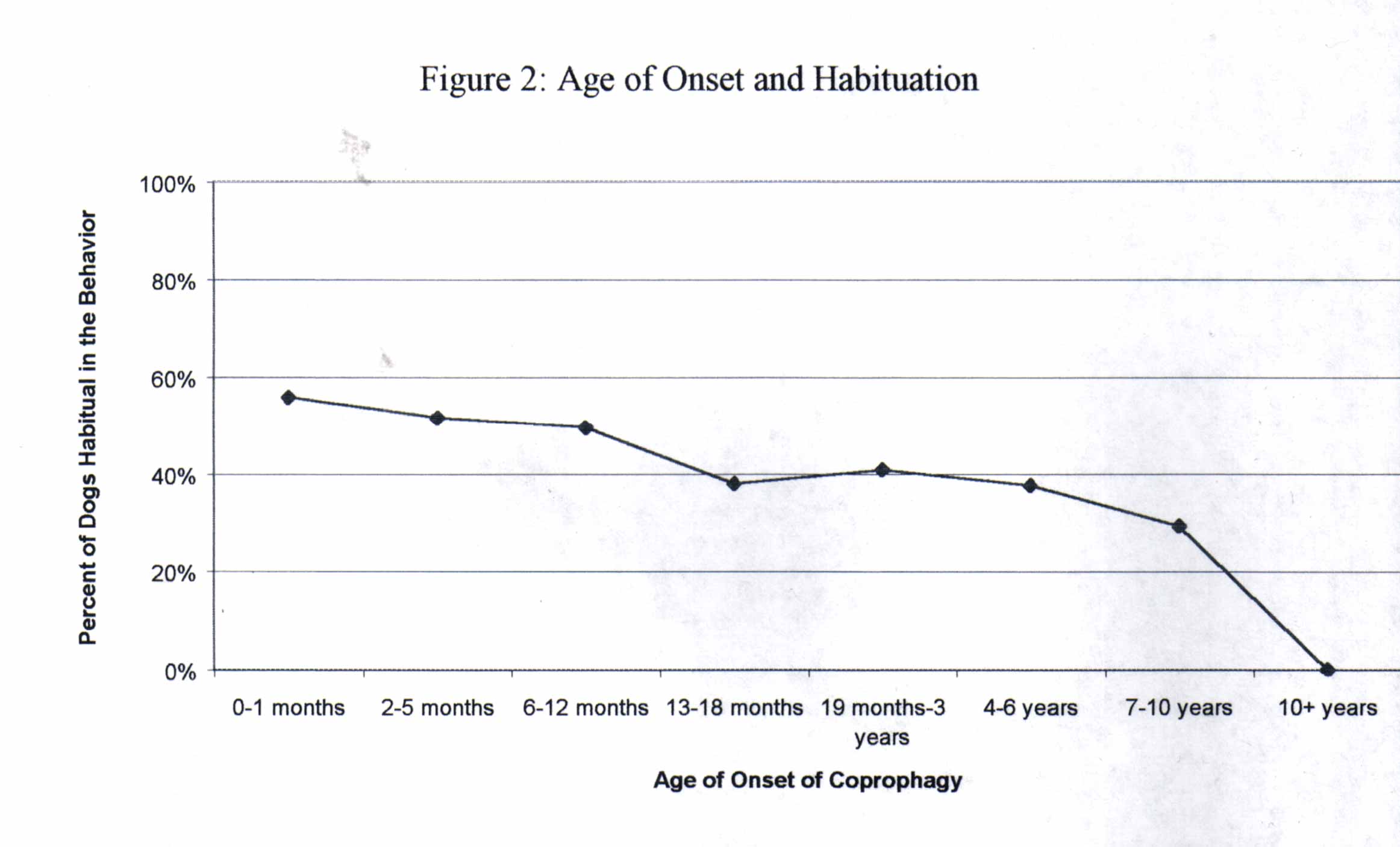

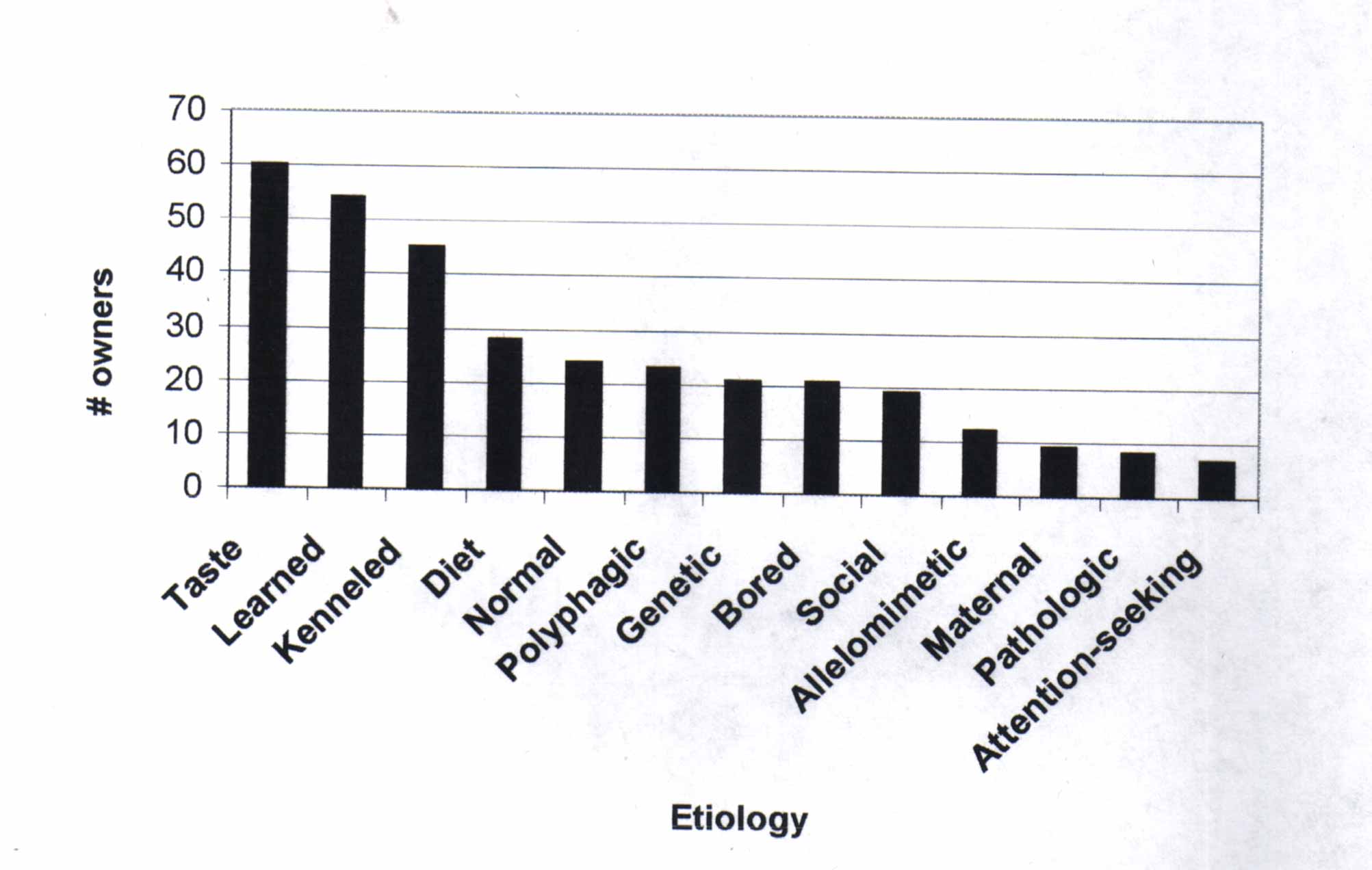

Of 682 owners of coprophagous dogs, 91.5% reported that their dogs’ behavior disturbed them. Four-hundred one (59%) owners reported that they talked with their veterinarian about coprophagy. Of these, 229 (57%) reported that their veterinarian was able to provide information that the owner considered helpful. Owners believed that desirable taste, being kenneled, and learning the behavior from other dogs were the predominant causes for their dogs’ behavior (Figure 3).* Added to food or administered orally

Figure 3. Owner reports of what they believe caused their dog(s) to be coprophagous. “Taste” = dog eats feces because it tastes good to him, “Kenneled” = dog was kenneled extensively as puppy, “Normal” = owner believes this is a normal canine behavior, “Polyphagic” = owner believes dog consumes everything, such as toys, grass, feces, etc., “Social” = dog engages in behavior during particular social circumstances with other dogs, “Allelomimetic” = copying owner’s behavior of picking up feces, “Pathologic” = secondary to some systemic disease (exocrine pancreatic insufficiency, etc.).One-hundred five out of 203 (52%) intact females had whelped at some point in their lives. Of these, 98 (93%) consumed their puppies’ feces.

Very few significant

differences

were observed between coprophagous dogs and non-coprophagous dogs, and

there were very few significant differences between coprophagous

groups.

This lack of difference suggests that coprophagy may be a normal

behavior

and is not associated with gender, age, breed, diet, housing, or

presence

of multiple dogs in the household. Autocoprophagous dogs weigh

less

than dogs who do not engage in autocoprophagy. The significance

of

this finding is not known, but suggests that dogs which weigh over

51lbs

are less prone to engage in autocoprophagy.

More allocoprophagous dogs

had access to other dogs’ feces than non-allocoprophagous dogs.

It

may be that non-allocoprophagous dogs, because of greater access to

other

species’ feces (cat, deer, horse, cow, etc.), chose those species’

feces

preferentially. It is also possible that non-allocoprophagous

dogs,

because of lack of access to other dogs’ feces, had less opportunity to

engage in allocoprophagy.

Approximately half the dogs in this survey were habitual in the behavior, and habitualness appeared to decrease in incidence as age of onset of the behavior increased. This may represent a delineation between normal behavior (i.e. dogs which are non-habitual in the behavior) versus pathologic behavior (i.e. dogs which are habitual in the behavior).

The most effective treatments described by owners were picking up feces, muzzling, and distraction. Additives worked inconsistently or not at all. This supports the supposition that coprophagy is difficult to treat with simple diet modifications or additions. A more interactive, direct intervention may be necessary to produce a successful outcome in the treatment of coprophagy.

It should be noted that treatment questions were asked only of owners of dogs who are currently coprophagous. Hence, it is possible that a treatment has been effective in coprophagous animals who were non-coprophagous at the time of the survey. In the treatment efficacy question, owners presumably interpret “treatments worked” as treatments which historically have ceased the behavior or treatments which reduce the incidence or severity of the behavior.

Unsurprisingly, the vast majority (91.5%) of owners of coprophagous dogs were disturbed by their dogs’ behavior. Despite this, only slightly more than half of these owners spoke with their veterinarian about coprophagy. This may represent a perception on the part of the populace that veterinarians are incapable of providing information or treatment recommendations about coprophagy. It may alternatively represent that owners do not consider coprophagy a medical condition or a condition that needs to be addressed by a veterinarian. Of those owners who did speak with their veterinarian about coprophagy, slightly more than half of these veterinarians were able to provide information. This implies a paucity of knowledge on the part of the veterinarian with regards to coprophagy, a situation made more difficult due to the lack of research into this behavior.

Most of the females which had whelped ate the feces of their puppies. This is consistent with the maternal etiology of coprophagy (Houpt 1991, Hubbard 1989). Due to ambiguous formation of subsequent questions of these dogs in our survey, however, we cannot make any further conclusions as to whether coprophagy following parturition was a cause of long-term coprophagy.

As with all non-compulsory surveys of a population, a natural selection bias exists in our sample because owners self-select for participation. Individuals who own or have owned coprophagous dogs are more inclined to reply to requests to fill out a coprophagy-related questionnaire, as evidenced by the greater number of coprophagous dogs (n=862) compared to non-coprophagous dogs (n=295) in our survey. Since we used the Internet to acquire data, a natural bias exists towards individuals who use the internet. A recent veterinary publication solicited information via the internet and had notably fewer cases (McCobb et al. 2001). A publication in the human medical literature documents that World-Wide-Web compliant software was valid and of comparable quality to pencil-and-paper collection (Bliven et al. 2001).

Further research into the behavior of coprophagy is required to determine if a definitive etiology exists. Prospective, randomized, double-blinded studies are required to document the true efficacy of any treatment protocol. Such goals are clearly outside the scope of this paper.

In conclusion, coprophagous

dogs

have very few observable characteristics which distinguish them from

non-coprophagous

dogs. Some of our data is consistent with the concept that

coprophagy

is a natural behavior in dogs, whereas other data from this study

contradicts

that idea. The treatments owners reported as being most effective

in treating coprophagy were to prevent access, distract the dog from

the

feces, muzzle, and picking up feces before the dog could access it.

Barnes

R.H.,

Fiala G. (1957) Nutritional implications of coprophagy. Nutrition

Reviews;20:289-290.

Beerda B.,

Schilder M., van Hooff J., de Vries H.W., Mol J.A. (1999) Chronic

stress in

dogs subjected to social and

spatial

restriction. I. Behavior Responses.

Physiology &

Behavior;66:233-242.

Bliven B.D.,

Kaufman S.E., Spertus J.A. (2001) Electronic collection of

health-related

quality of life data: validity,

time benefits, and patient preference. Quality of Life

Research;10(1):15-22.

Campbell

W. (1975) The stool-eating dog. Modern Veterinary

Practice;56:574-575.

Cloche D.

(1991)

Coprophagy in dogs. Tijdschrift voor diergeneeskunde;116:1256-1258.

Georgi J.R.,

Georgi M.E., Fahnestock B.S., Theodorides V.J. (1979) Transmission and

control of Filaroides hirthi

lungworm

infection in dogs. American Journal of

Veterinary Research;40:829-831.

Houpt K.

(1982) Ingestive behavior problems of dogs and cats. Veterinary Clinics

of

North America: Small Animal

Practice;12:683-692.

Houpt K.

(1991) Feeding and drinking behavior problems. Veterinary Clinics of

North

America: Small Animal

Practice;21:281-298.

Hubbard B.

(1989) Flatulence and coprophagy. Veterinary Focus;1:51-54.

Kronfeld

D.S. (1973) Diet and the performance of racing sled dogs. Journal of the

American Veterinary Medical

Association

;162:470-473.

Landsberg

G.M. (1997) Handbook of behavior problems of the dog and

cat.

Boston:

Butterworth Heinenann; 112-114.

McCobb E.C.,

Brown E.A., Damiani K., Dodman N.H. (2001) Thunderstorm phobia in

dogs: An internet survey of 69

cases.

Journal of the American Animal Hospital

Association;37:319-324.

McCuistion

W.R. (1966) Coprophagy: a quest for digestive enzymes. Veterinary

Medicine, Small Animal

Clinician;61:445-447.

McKeown D.,

Luescher A., Machum M. (1988) Coprophagy: food for thought. Canadian

Veterinary Journal;29:849-950.

Pijls

J.L., van der Gaag I., Shanasa S.S. (1988) A rare case of juvenile

atrophy

of the

pancreas. Tijdschrift voor

diergeneeskunde;113:607-613.

Read D.H.,

Harrington

D.D. (1981) Experimentally induced thiamine deficiency in

beagle dogs: clinical

observations.

American Journal of Veterinary

Research;42:984-991.

Soave O.,

Brand

C.D. (1991) Coprophagy in animals: a review. Cornell

Veterinarian;

81(4): 357-364.

Name:

Your email:

City and state of dog’s location:

What is the dog’s breed:

What is the dog’s sex?

Is the dog spayed/castrated?

3) How old is the dog?

0-1

months

2-5 months 6-12 months

13-18 months 19 months-3 years

4-6

years

7-10 years 10+ years

What is the dog’s weight?

0-5

pounds

6-10 pounds 11-20

pounds

21-35 pounds 36-50 pounds

51-70

pounds

70+ pounds

What is the dog’s diet mostly

composed

of?

Premium Diet

(Iams, Eukanuba, Hill’s, Waltham, etc.) Cat

Food

Prescription

Supermarket-bought

Specialty (Pitcairn, vegetarian, home-made, etc.)

Other

(Describe):

Where does the dog spend most

of

its time?

Indoor/outdoor

Kennel (outside) Crate

(inside)

Home (inside)

Yard

(outside)

Other

Does more than one dog live in this household?

Does the dog have any medical conditions? If so, what are they?

Is this dog on any medications

(this

includes Program, Advantage, Heartguard, etc.)?

If so, what are they?

Please indicate if the dog has

access

to any of the following feces:

Other

Dogs

Cats Deer

Horse

Cow His/Her Own

Does not have

access to any feces

Other

(Describe):

Does the dog eat other species’ feces?

If so, specify what type:

Cat

Deer Horse

Cow

Other (Describe):

Does the dog eat other dogs’ feces?

Does the dog eat his/her own feces?

If the dog does not eat feces,

the

questionnaire is completed. Thank you very much.

When the dog has the opportunity to eat feces, does he/she always do so?

What was the age of the dog

when

it began eating feces?

0-1

months

2-5 months 6-12 month

13-18

months 19 months-3 years

4-6

years

7-10 years 10+ years

Does it disturb you that the dog engages in this behavior?

Have you talked to your veterinarian about this behavior (coprophagy)?

Was your veterinarian able to assist you or give you information about this behavior?

What have you done to stop the

dog

from eating feces (check all that apply)?

Meat

tenderizer

Papaya

enzyme

Forbid

Spinach

Deter

Breath

mints

Anise seed/liquid

Picking up

immediately

Ignoring

Pineapple

DisTaste

Muzzle

Distracting the dog

Scolding/punishment

Greenbeans

Pumpkin

Nothing

Bad taste on

feces (hot sauce,

etc.)

Other (Describe):

Which of these treatments

seemed

to work (check all that apply)?

Meat

tenderizer

Papaya

enzyme

Forbid

Spinach

Deter

Breath

mints

Anise seed/liquid

Picking up

immediately

Ignoring

Pineapple

DisTaste

Muzzle

Distracting the dog

Scolding/punishment

Greenbeans

Pumpkin

Nothing

Bad taste on

feces (hot sauce,

etc.)

None Worked None Tried

Other

(Describe):

Has the dog ever whelped?

If so, did she consume the puppies’ feces while nursing?

Why do you think your dog is coprophagous?

If there were any changes to the environment (new people, new place, etc.) or changes in the dog’s medical condition when the dog began eating feces, please describe those below.

If you have any additional

comments,

please use this space to discuss them.